What happened to art?

Many visit galleries expecting to see Renaissance-esque paintings around every corner, only to leave asking themselves the question above.

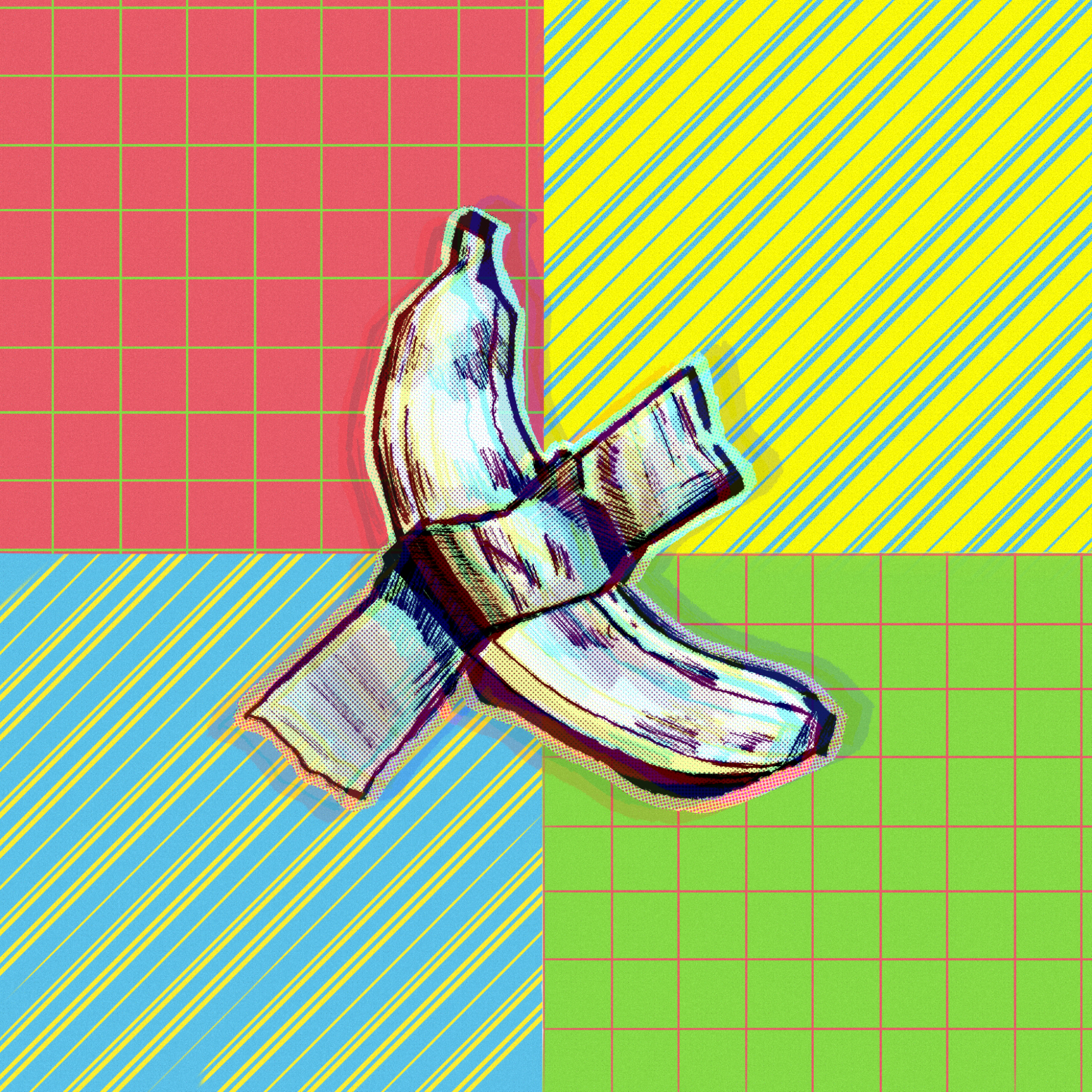

Indeed, after wandering through collections of detailed portraits, intricate landscapes, and stunning still-lifes, they find…scribbles? Splotches of paint? A banana taped to the wall? It seems a little too outrageous to be true, but upon checking that little museum placard, viewers are forced to reckon with the fact that yes, the banana taped to the wall is a real exhibition, and yes, that banana sold for 6.2 million dollars at an auction.

In a society that correlates hard work with skill and success, these absurd, “talentless” pieces with equally absurd price tags feel cheap and soulless. They feel even cheaper when contemporary art connoisseurs desperately argue that no, that isn’t just a banana taped to the wall, it’s actually a commentary on consumerism and what we value–obviously.

When looking at contemporary exhibits and then looking at pieces from bygone eras, the difference is startling. How do we compare the banana on the wall to these stunning compositions and remarkable achievements in technical skill? When discussing history’s greatest artists, how can we include Basquiat, Pollock, and Warhol in the same conversation as Michelangelo and Leonardo da Vinci?

Many people would argue that modern and contemporary art isn’t “real art” at all and that these movements demonstrate a regression in talent. In an article for The Forum, Wilton High School sophomore Nino Jaliashvili argues that modern art “…has turned into a way for people to get rich without making any actual art.” This perspective, however, fails to acknowledge that, regardless of the price tags, modern and contemporary art are a testament to human creativity and our ability to respond to broad social, cultural, and political changes.

All artistic movements are influenced by the changes occurring in society at large.

Renaissance art, for instance, was a product of the general intellectual mood in Europe at the time; the classical subjects depicted in the works of Italian artists mirrored Italian society’s fascination with classical learning.

The modern art movement, which started in the late 19th century and stretched to the mid-20th century, was not just a response to change: it was an attempt to grapple with the complete rearrangement of society.

The Industrial Revolution fundamentally altered standard ways of living as efficient assembly lines replaced humble means of production. Innovations in technology brought people to cities and changed the way humans interacted with each other, markets, and entire ecosystems. The world reaped the benefits of industrial advances, but it also witnessed the devastating effects of these breakthroughs when two World Wars ravaged the continent of Europe.

In the aftermath of these wars, long-standing institutions and perspectives crumbled. Artists, however, breathed new life into their respective mediums, using their art to reckon with chaos and confusion.

In literature, the flowery language of the 19th century shifted toward explicit, stream-of-conscious style writing intended to explore the human psyche. Likewise, visual artists utilized novel techniques, abstracting figures beyond recognition and seeking to capture ideas and emotions, rather than realistic depictions of the world around them.

As modern art grew increasingly experimental, more and more people began to ask the question: what made things art in the first place?

Evidently, this was a question many were unwilling to answer. Although several modern artists earned a name for themselves, their art was not universally embraced. When Joan Miró unveiled his work at a solo show at the Dalmau Gallery in 1918, observers vandalized and ridiculed the collection. Cubism’s very name derives from the words of one Louis Vauxcelles, who argued that Braque’s geometric, simplified works paled in comparison to the detailed, traditional paintings of years prior.

Today, critics and average onlookers alike remark that “a five-year-old could make that” when staring at Matisse’s cutouts, Mondrian’s squares, and Twombly’s scribbles. People are just as hostile to contemporary pieces, like the banana on the wall, and why wouldn’t they be? The ridiculous price tags and the elitist culture surrounding this type of art frustrate casual enjoyers expecting refined exhibitions.

But why is the price tag the first thing people look at? Is there any way we can appreciate these pieces simply for their creativity and experimentation?

It’s interesting that the default insult hurled against contemporary artists is that their work is no better than a child’s. Children have enormous creative potential, and parents practically turn their refrigerators into art galleries. Society celebrates unrestricted creativity at one age while condemning it at another, because apparently, “real” artists need to have “real” ideas.

Nathan J. Robinson, editor-in-chief for the magazine Current Affairs, refutes this expectation. As he puts it in an article, “Great art doesn’t need to come from singular geniuses. Maybe we can all do it. And we should.”

You don’t have to like modern and contemporary art. Regardless of personal preference, however, these movements are real art, and saying otherwise is an affront to creativity.