School has destroyed learning.

50 years ago, people learned for the fun of it. They wanted to learn more about their interests or to contribute to society with college emerging as an afterthought. Now college, not interest, primarily drives learning, and not without reason.

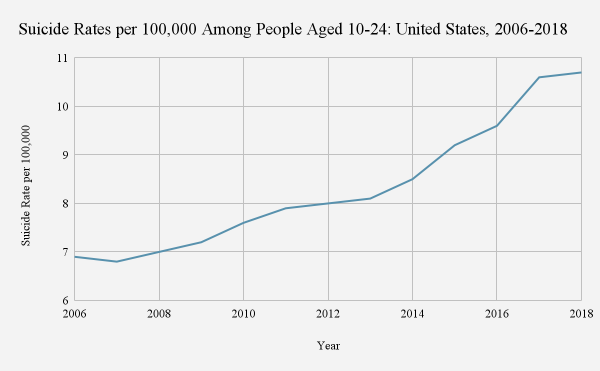

College applications have transformed into an increasingly difficult race to get to the top. From 2006-2018, acceptance rates at the top 51 colleges in America decreased from 35.9% to 22.6% while at the top 10 rates dropped from 16% to 6.4%. This pushes students to their limits, leaving those who can’t keep up in the dust, feeling inadequate. Not surprisingly, during this same time frame, suicide rates among 10-24 year-olds increased by 55%.

Clearly, this is a problem.

Many students get caught up in this race, taking honors classes whenever possible, sacrificing the freedom to choose their courses, and with it, their love of learning.

“I take pretty much all of my classes either because of my parents or to look good on college applications,” says Leonardo (Leo) Kulon, a sophomore student at WHS who takes multiple honors classes. “I take AP Computer Science because I am interested in it but that is about it.”

Kulon, like many others, feels that taking honors classes “is a chore” that he would rather be without. For him, the pressure of higher education has choked out the possibility of enjoying education. Teachers, as well as students, recognize this pressure.

Tim Donahue, a high school English teacher who interacts with stressed-out students on a daily basis, writes in his essay, “We have pushed high school students into maximizing every part of their days and nights. Those who take the bait are remarkably compliant, diluting themselves between their internships and Canva presentations. We condition students to do a so-so job and then move on to the next thing. We need to let them slow down. Critical cognition, by definition, takes time.”

In addition to suggesting that schools overwork students, Donahue also asserts that this limits the quality of learning that they receive. This, in turn, exacerbates the problems caused by screens, lack of social connection, and mental health.

Basically, students receive lower-quality learning in exchange for worse mental and social health. The problem stems from the changing attitude towards learning as something with a concrete goal rather than an abstract one. The result? What once fostered enjoyment, now fosters dread.

Some students disagree.

Lochlain Steere, a former student of the Urban School in San Francisco, tells students to “Stop complaining about school, you signed up for this” and urges students to reconsider their approach to their own education. She argues that students should appreciate the effort that goes into funding their education and making things possible, rather than complaining all the time. They just have to deal with the cons of an otherwise good system.

While this tough-it-out method may work for some students, it doesn’t actually attack the problem at the source, making it really ineffective and dependent on the student. If we really want to fix it, we will have to look somewhere else.

Harry Zhou, another WHS sophomore student (and peer of Kulon’s) who takes even more honors classes, explains, “I personally enjoy learning in school, but I understand why many do not…I enjoy the faster pace [of honors classes], and you get a lot more from the class.”

This attitude certainly exists among students who can retain their love of learning despite growing post-secondary pressures, however, the changing educational landscape still affects them.

For example, both Zhou and Kulon agree that grades can be overwhelming.

Kulon claims that he overemphasizes grades “All of the time; that is the only thing that matters.”

Zhou, more cordially, also concedes that he focuses on grades too much, stating, “[grades] definitely take away from the joy of learning. Focusing on grades as a number is very inhibiting.”

The effect of grades goes beyond simply removing joy from learning or becoming a time-consuming pursuit; it actually brings fear.

“For some, fear of failing can lead to paralysis which makes it hard to get started on projects. They’d rather be considered lazy or defiant than dumb,” writes Jeannine Jannot in The Disintegrating Student. This can have a drastic effect on students and their well-being.

This mentality consumes students’ minds, ultimately making them feel terrible, perform poorly in school, and sever social relationships. Overall, their lives get worse.

So what do we do about it?

Unfortunately, we cannot remove the grading system, we cannot stop going to school, and we cannot force colleges to accept more students. We can, however, give students a positive learning experience: one that will encourage them to explore and satisfy everyone.

To do this, schools should implement an annual project that tries to embody these core educational values. Take a week off from regular classes and have students explore a topic that interests them, not what interests the curriculum. Their homework should consist of only this project which is graded solely on effort, pass-fail. While having a grade could be discouraging at first, it is necessary to make sure students do the assignment earnestly. The learning experience will not be diminished as people will have the freedom to do whatever they want. As long as they engage with their project they should pass. College will never come into the picture.

By doing this, students will get a taste of the educational experience people once appreciated and they just might discover something new and rekindle their love of learning.